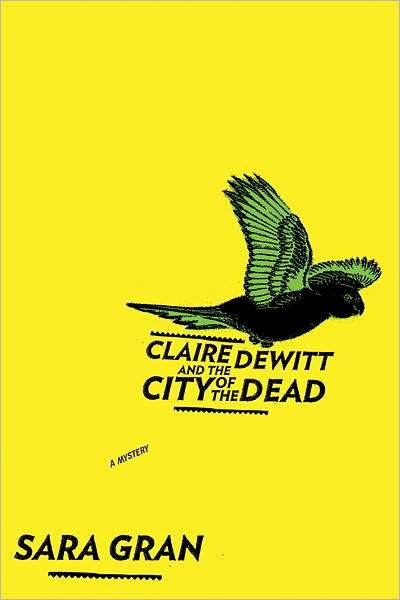

Praise for CLAIRE DEWITT AND THE CITY OF THE DEAD

“This is not to be missed-Claire is a moody, hip, and meticulous investigator. Gran (Dope; Come Closer) builds an addictive sense of anticipation with a fantastical frame. Alternately gritty and dreamy, this would appeal to those who liked Colson Whitehead’s The Intuitionist and readers of Charlie Huston (e.g., The Mystic Arts of Erasing All Signs of Death). Highly recommended.” —Library Journal, STARRED

“Captivating.” —Publishers Weekly, STARRED

“If there isn’t yet a subgenre called funky noir, this wacky PI novel could be a fragrant first…lots of fun.”—Booklist

“Gran (Dope, 2006, etc.) provides…a comically self-important detective and a searing portrait of post-Katrina New Orleans.” —Kirkus

“Terrific. I love this book! Absolutely love it. This is the first fresh literary voice I’ve heard in years. Sara Gran recombines all the elements of good, solid story-telling and lifts something original from a well-loved form.” —Sue Grafton

CLAIRE DEWITT

And the

CITY OF THE DEAD

by Sara Gran

June 02, 2011

Tour cities: San Francisco, Phoenix, New Orleans, New York

Sara Gran’s entrance into mystery-writing is a big one with this first in a brand new series, CLAIRE DEWITT AND THE CITY OF THE DEAD (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, June 2, 2011). Gran introduces an intriguing, strong female character named Claire Dewitt—she’s a tattooed, pot smoking badass who uses the “get down and dirty” approach to detective work. The best part is that she is, according to Gran, largely autobiographical: “Of all my books this is both the most autobiographical and the most fantastical. I grew up, as Claire did, the crime-ridden Brooklyn of the 1970s and 80s. Like Claire, I was in New York City on 9/11 and I lived in New Orleans after (and during) Katrina. And like Claire, my own life story was (and is) a mystery to me. But Claire lives in world just a hair to the side of ours—a world where warring schools of detection define a detective’s life, where synchronicities and omens solve crimes, where fingerprints are read not just for IDs but, like tea leaves or palm, for secrets and signs. Or maybe that really has been our world, all along—just like this one, only a little more interesting—but most of the time, our eyes weren’t open wide enough to see.”

In the story, Claire uses advice from Detection, the only book ever published by the great, mysterious French detective, Jacques Sillette, to investigate the disappearance of prosecutor Vic Willing in post-Katrina New Orleans. Claire meets a powerful cast of characters along the way, including and especially the youth on the streets, who just might hold the key to the whole mystery. Gran’s portrayal of that youth is heartwrenchingly realistic, with eye-opening depictions of young children stealing and killing in order to feed their family members.

“But,” says Gran. “It’s not about the government. When I tell people I lived in New Orleans in 2005, or that I’ve written a novel set in post-Katrina New Orleans, people quickly start talking to me—telling me, usually, as if I hadn’t been there—about the government and its failings, about FEMA, about the depth of the levee pilings and the billions in damage done. Things should be back to normal by now, people rush to say, indignant. But after a few years I noticed there is not only a rushing too in these calculations—a rush to assign blame, to solve problems. There is also a rushing away—a turn away from the sorrow of a city where thousands have died and thousands more were been left behind. Numbers and facts are necessary. But they’re also a distraction from what may be the most important legacy of Katrina—psychological and spiritual trauma, and how we live with it. Or don’t.

Facts and figures can help us understand the truth. Equally they serve to hide the truth, not from others but from our own private selves.

New Orleans’ famously high crime may be symptom—or a symbol—of this dual urge: the rush to blame and the rush to avoid facing our well-earned pain. After Katrina there was a frightening rise in violent crime in New Orleans. Crime in New Orleans is not new—young people are abandoned by parents to a spectacular degree, violence has become normalized, and educational and economic opportunities have been slim. (And before you get excited about the low unemployment numbers for New Orleans recently, keep in mind those numbers explicitly leave out those who have, after a lifetime of poverty and rejection, given up looking for work.) In talking about the upswing in violence, people blame the police force, new drug distribution trends, the availability of weapons—all well and good.

But such conversations miss an important point. After undergoing a disaster, after being left behind by the entire world, after being clearly told that, in case they had somehow not yet gotten the point, they do not matter to us, we should not be surprised that some people come to feel so frightened and alone that they will truly believe they must shoot the other guy before he shoots first–or that many people loathe themselves so completely they will eagerly kill another who looks like them. This does not absolve such people of responsibility for their actions. But it does call into question exactly what they’re to be held responsible for.

This is not a popular topic of discussion. But the government, people tell me, these well-meaning people who, despite never having been to New Orleans, are happy to tell me all about it. The government didn’t do what they were supposed to do. True enough. But the government cannot heal broken hearts. This is the job of each human alone.

We have spent five years talking about money and rebuilding and slab foundations and evacuations and blue roofs. Rarely do use the words sorrow or sadness in talking about the storm. 1800 hundred people lost and all anyone wants to talk about is FEMA.

“Paradoxically,” Tanya Wilkinson writes in her brilliant Persephone’s Return: Victims, Heroes, and the Journey from the Underworld, “mourning must be embraced if it is ever to be finished.”

Nothing will ever be normal again; this truth is gigantic and awful and very difficult to understand. There have been few novels so far that deal with the storm—maybe this is why. What we have to say is likely not what anyone wants to hear. But we will tell our stories anyway, eventually, and maybe it will fall to us, in the years to come, to tell the real story of Katrina—not who we blame for what but what it looked like, sounded like, and most of all, felt like, different for each of us and no two stories alike. Maybe this will be our mourning and maybe, although things will never go back to the old normal, maybe things can better.

Or maybe people will keep ignoring us and keep up their cry; The government, they will say. Don’t you want to talk about the government?”

Sara Gran‘s previous novels include Come Closer, a psychological thriller hailed as “hypnotic, jdisturbing…genuinely scary” (Bret Easton Ellis), and Dope (“highly recommended,” Lee Child). Television rights to Claire DeWitt have been bought by Fremantle (the company that brought you American Idol) and the Todd Sisters (responsible for Memento, Boiler Room, and all three Austin Powers films). A former bookseller and native of Brooklyn who lived in New Orleans during Katrina, she now lives in northern California.

Sara Gran on Tour

SAN FRANCISCO

Copperfield’s Bookstore, Friday, June 3, 7:00p.m.

M is for Mystery Bookstore, Sunday, June 5, 2:00p.m.

PHOENIX

Changing Hands, Monday, June 6, 7:00p.m.

Poisoned Pen Bookstore, Tuesday, June 7, 7:00p.m.

NEW ORLEANS

Garden District Boosktore, Thursday, June 9, 5:30-7p

Octavia Books, Saturday, June 11, 6p.m.

NEW YORK

Greenlight Books, Monday, June 13, 7:30p.m.

CONTACT: Michelle Bonanno, Publicist

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

617.351.3832 ph

617.351.1109 fx

michelle.bonanno@hmhpub.com