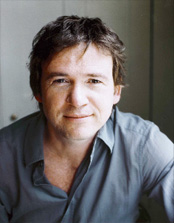

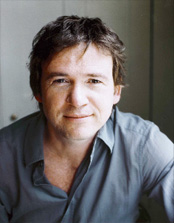

David Nicholls is the author of the international bestseller One Day, a novel that checks in with two friends, Emma and Dex, every July 15 from their first meeting, the night of their college graduation in 1988, up to the present day, as their relationship blossoms, stumbles, and evolves. He’s also the screenwriter for the film version of the novel, starring Anne Hathaway and Jim Sturgess, which opens in U.S. theaters on August 19. What was it like for Nicholls to transpose his story to another medium? “There’s a tendency to feel that because you’ve written the book, because you know the book better than anyone else possibly could, that you should have final say,” he said during a recent visit to New York. “[But] you can’t constantly pull rank and say you worked on the book, you have to accept that some things you love, that you relate to very personally, aren’t necessarily going to make it to the screen.”

David Nicholls is the author of the international bestseller One Day, a novel that checks in with two friends, Emma and Dex, every July 15 from their first meeting, the night of their college graduation in 1988, up to the present day, as their relationship blossoms, stumbles, and evolves. He’s also the screenwriter for the film version of the novel, starring Anne Hathaway and Jim Sturgess, which opens in U.S. theaters on August 19. What was it like for Nicholls to transpose his story to another medium? “There’s a tendency to feel that because you’ve written the book, because you know the book better than anyone else possibly could, that you should have final say,” he said during a recent visit to New York. “[But] you can’t constantly pull rank and say you worked on the book, you have to accept that some things you love, that you relate to very personally, aren’t necessarily going to make it to the screen.”

Nicholls was already comfortable with this process, though, as he’d been writing for TV shows in Britain before he turned to prose fiction. “When you work in television, you become very tough about throwing things away, about discarding material,” he explained, “and that’s something I’ve had to do in adapting my own work. The emphasis always has to be on story, always has to be on moving things forward.”

In the novel, for example, Emma’s state of mind through many of the early chapters is largely aimless: She’s still looking for the motivation to find a job, a decent apartment, a boyfriend. “On screen, it’s a little repetitive, it’s a little static,” Nicholls says. “It’s very hard to dramatize someone being stuck, so you have to be a lot more deft and economical with that kind of material. You have to establish her situation and her state of mind and then move on to stuff that is more active, material that gives the movie more forward momentum.”

In the novel, for example, Emma’s state of mind through many of the early chapters is largely aimless: She’s still looking for the motivation to find a job, a decent apartment, a boyfriend. “On screen, it’s a little repetitive, it’s a little static,” Nicholls says. “It’s very hard to dramatize someone being stuck, so you have to be a lot more deft and economical with that kind of material. You have to establish her situation and her state of mind and then move on to stuff that is more active, material that gives the movie more forward momentum.”

The novel also keeps Emma and Dex apart in some early chapters, staying in touch with each other through letters. (Remember, it’s the late 1980s and early 1990s, before email.) But, as Nicholls puts it, “there’s nothing cinematic about a letter,” so he came up with a short scene, set the year after their first night together: Dex helps Emma move into her London apartment, even though he’s in a hurry to get to the airport for an international flight. It’s a quick bit of business, but it tells viewers everything they need to know about how their friendship has progressed.

One thing that didn’t change in the transition from book to film, though, is the structural constraint of only seeing the characters on July 15. On the printed page, that gives every chapter a built-in cliffhanger, but how would that translate to the big screen? Would the year-long gaps come off as disjointed and choppy?

Nicholls did worry about that when he began the screenplay. “As a novelist, you can say, ‘Six months before, Emma had bumped into Ian on Tottenham Court Road,'” he explained. “On screen, you can’t do that sort of very basic straightforward exposition.” Although he included explanations in the screenplay for how Emma finally becomes a writer, or how Dex met his wife, the final version has only a fraction of that material. “We found that it was more fun not to worry too much about the exposition, just to show the characters one year later and that the audience would fill in the gaps themselves.”

Nicholls did worry about that when he began the screenplay. “As a novelist, you can say, ‘Six months before, Emma had bumped into Ian on Tottenham Court Road,'” he explained. “On screen, you can’t do that sort of very basic straightforward exposition.” Although he included explanations in the screenplay for how Emma finally becomes a writer, or how Dex met his wife, the final version has only a fraction of that material. “We found that it was more fun not to worry too much about the exposition, just to show the characters one year later and that the audience would fill in the gaps themselves.”

It works: Not only does the film make smooth transitions from one year to the next, but Hathaway and Sturgess are able to age gracefully into their parts, giving Emma and Dex’s emotional journey a compelling credibility. If you’ve read One Day already, you will recognize the core of the novel underneath the layer of cinematic alterations. If this is your first experience with the story, you’ll quickly find yourself sucked into the drama, anticipating the changes of each coming year and wondering how Dex and Emma will handle the latest developments.

—Ron Hogan helped create the literary Internet by launching Beatrice.com in 1995. His most recent book is Getting Right with Tao, a print edition of his popular online “translation” of the Tao Te Ching into modern vernacular.

He is also the author of The Stewardess Is Flying the Plane, a visual tribute to ’70s Hollywood, and a contributor to several anthologies, including the New York Times bestseller Not Quite What I Was Planning, Forgotten Borough: Writers Come to Terms with Queens, and Secrets of the Lost Symbol.