By: Steven James

When I started writing, I never realized that I wouldn’t so much be creating the characters for the stories that I write as I would be letting them speak for themselves. It’s almost as if my job is to let them reveal themselves to me and then be honest to the reader about who they really are.

Odd. I know. But that’s how things have played out.

Eight years ago when I was writing my first psychological suspense novel, The Pawn, I remember sitting on the back porch reading through a first draft of one scene in which Tessa, the main character’s teenage stepdaughter, appeared. She seemed whiny and one-dimensional and I just wasn’t interested in her. I didn’t like her. I didn’t care much what happened to her.

But then, as I worked on the story, it was almost like I could hear her tell me, “That’s not what I’m like. You don’t know me yet. Let me show myself to you.”

So, as I wrote, I tried to let her do that and, sure enough, she began to emerge—a girl who was whip-smart, witty and independent, but also emotionally wounded and searching for answers. Her inconsistencies intrigued me. There was so much more to her than I would have ever thought. After that, she vied for a bigger part in the next novel, The Rook, and I had to give it to her.

She’s been around the series ever since and, from what many readers tell me, she’s one of their favorite characters.

But it’s not just her.

It’s happened with other bit characters who I thought would just appear in one book, and then fade away, but they lobbied my subconscious or picketed my imagination to have a bigger part in the next book. At times I fought against this, and when I did, the story suffered. But when I gave in and let the characters be themselves and have their way, the story resonated as being more honest.

I know it sounds a little crazy—after all, I’m supposed to be in control, right?. I’m the author, the guy who’s job it is to make this stuff up. Not the characters.

The problem is: sometimes my characters don’t like how they’re being portrayed and they’re not ashamed to tell me so. And, since they live in my head, they won’t leave me alone if I don’t give them what they want.

It’s annoying.

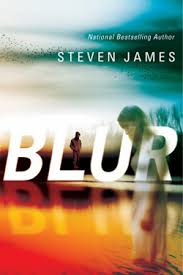

Recently I wrote a teen thriller called Blur. When high-school football star Daniel Byers begins to have visions relating to the suspicious death of a girl at his school, he and his friends question whether he’s mentally ill or gifted with a psychic ability that could lead them to solve the mystery.

As the gritty mystery unfolds, Daniel slowly begins to lose touch with reality. Writing his story, I glimpsed what it would be like to be trapped on the avenue to madness. It’s the place where reality and fantasy blur, the place where you can’t tell where the line is between what your mind is telling you is real and what other people are telling you is real.

It’s sort of the place I make a living.

So maybe it’s not so bad—this whole deal of living with imaginary characters who tell me what to do. I supposed the journey into a story is it’s own kind of anointed madness. And I’m just glad I can invite other people along for the ride.

You can learn more about Steven’s novel Blur here