Mary Breckinridge – a Woman with a Vision

Mary Breckinridge – a Woman with a Vision

by Ann H. Gabhart, Author of An Appalachian Summer

Have you ever wished you could do something to make a difference in the world? We may see something that should be changed. Perhaps we even think of ways these changes could happen but then we feel as if the task is too big, too hard for one person to accomplish. But there are people who don’t give up, but work with determined zeal to realize their visions of helping others. Not long ago while researching for a new idea for a historical novel, I came across such a person, Mary Breckinridge.

Mary Breckinridge was born into a socially prominent family. It was while her father served as an ambassador to Russia that Mary had her first encounter with a midwife who delivered her little brother. Later, she experienced tragedy in her life, being widowed at a young age. She remarried and had two children. In 1916, her baby girl, born prematurely, only lived a few hours. Two years later her son died at the age of four from appendicitis. This might have embittered some women, but Breckinridge set out to live a life of service. She had trained as a nurse before her second marriage. After the death of her son, she traveled to France to help the citizens recover from World War I. There she witnessed the difference nurse midwives made in the lives of French citizens impoverished by the war. She decided nurse midwives could be the answer for healthcare needs in poverty stricken areas of America.

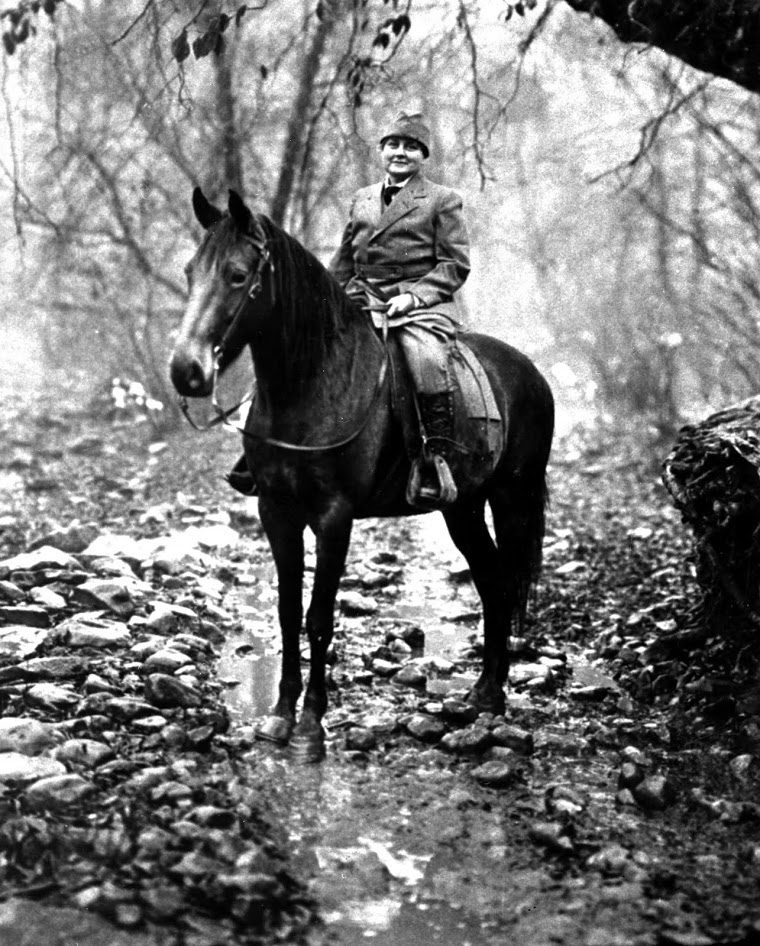

Perhaps due to her family’s Kentucky roots, she traveled by horseback through the Eastern Kentucky Mountains speaking to the people and granny healers to find the best place to establish a nurse midwife service for families with little or no access to medical providers. Breckinridge had a heart for children and for the mountaineers she considered admirable stalwart Americans.

She returned to England to get midwifery training since America had no midwifery schools at that time. In 1925 she established the Frontier Nursing Service as a private charitable organization serving 700 square miles in Eastern Kentucky. Known for her persuasive powers, she recruited English midwives to come serve the Appalachian people. These hardy recruits supplied prenatal childbirth care in their patients’ homes that were often primitive cabins with none of the conveniences we now consider necessities. Since there were no roads up into the hills at that time, the nurse midwives went by horseback or by foot to tend to their patients.

While the nurse midwives main purpose was healthcare for mothers and children, they treated all sorts of medical needs. Clients could pay the low fees in money or goods, but no one was ever turned away if unable to pay. Breckinridge, through her social connections and by speaking to groups of women about the work of her Frontier Nurses, raised over six million dollars to support her nurses and build centers throughout the area. After the nurse midwives began serving the area, maternal and infant mortality rates decreased dramatically. In the first fifty years of the Frontier Nursing Service, the nurse midwives delivered over seventeen thousand babies with only eleven maternal deaths.

When England became embroiled in World War II in 1939, the British midwives felt it their patriotic duty to return to England to serve their country. In order to continue her midwifery services in the mountains, Breckinridge established a midwifery school at the small Hyden Hospital she’d convinced the town to build in 1928. The Frontier Nursing University is still training healthcare workers today. (https://frontier.edu/)

To recruit women for her Frontier Nurses, Breckinridge promised them adventure and their own horse and dog to add to the opportunity of saving children’s lives. Nurses and midwives came and did just that.

In These Healing Hills, my first book with this inspiring Frontier Nursing history, my main character was a nurse midwife who did ride up into the mountain and provide prenatal care and deliver babies. But I wanted to write more about Mary Breckinridge and her Frontier Nurses, so I delved into the history of the Frontier Nurses again and this time my novel, An Appalachian Summer, features a volunteer courier. The couriers were young women, usually from well to do families, who volunteered to spend weeks or sometimes months in the Appalachian Mountains where they ran errands for the nurse midwives, took care of their horses, mucked out stalls, tended gardens, painted walls, or whatever was needed to free up the nurse midwives to care for patients. Sometimes these young women would accompany the nurse midwives on patient calls and witness babies coming into the world. Even though Mary Breckinridge had by then built her log house at Wendover and a Garden House for the couriers, electricity was no more than a hoped for convenience for many years.

In These Healing Hills, my first book with this inspiring Frontier Nursing history, my main character was a nurse midwife who did ride up into the mountain and provide prenatal care and deliver babies. But I wanted to write more about Mary Breckinridge and her Frontier Nurses, so I delved into the history of the Frontier Nurses again and this time my novel, An Appalachian Summer, features a volunteer courier. The couriers were young women, usually from well to do families, who volunteered to spend weeks or sometimes months in the Appalachian Mountains where they ran errands for the nurse midwives, took care of their horses, mucked out stalls, tended gardens, painted walls, or whatever was needed to free up the nurse midwives to care for patients. Sometimes these young women would accompany the nurse midwives on patient calls and witness babies coming into the world. Even though Mary Breckinridge had by then built her log house at Wendover and a Garden House for the couriers, electricity was no more than a hoped for convenience for many years.

The thought of pampered young women coming to the mountains to live in primitive conditions and to work at various dirty jobs started me down a new story road. I brought my young woman to the mountains where she “heard the whippoorwill and saw the stars.” Then, I made Mary Breckinridge a character too in order to highlight her strong will and her ability to get things done that made the Frontier Nursing Service such a success.

Recently I spoke with a woman who spent several years in the 1960’s as a nurse midwife with the Frontier Nursing Service. For her, it was a never to be forgotten experience. From what I’ve read about former couriers with the program, they felt the same. In fact, the position as courier became so sought after that there was a waiting list of applicants. Former couriers, wanting their daughters to have the experience of working with the nurse midwives, would add their daughters’ names to the waiting list as soon as they were born.

Wendover is now a National Historic Site and operates as a Bed and Breakfast. (https://wendoverbb.com/) Visitors can view  the Frontier Nursing Service history in the displays and pictures in the two story log house that was called the “Big House” while it was the Frontier Nursing Service headquarters. Also, Mary Breckinridge wrote her own autobiography, Wide Neighborhoods, first published in 1952. The book is still available and gives readers a great insight into what one woman with a vision can accomplish.

the Frontier Nursing Service history in the displays and pictures in the two story log house that was called the “Big House” while it was the Frontier Nursing Service headquarters. Also, Mary Breckinridge wrote her own autobiography, Wide Neighborhoods, first published in 1952. The book is still available and gives readers a great insight into what one woman with a vision can accomplish.

“No one comes here by accident.” That was a Frontier Nursing Service saying I made true for my nurse midwife in These Healing Hills and also for Piper, my volunteer courier, in An Appalachian Summer. The women who actually worked as nurse midwives and couriers also believed it was no accident they came to work with the Frontier Nursing Service. They were sure they were meant to be part of this wonderful service that did save mothers and children.

I think perhaps it was true for me too, as a writer of historical fiction. I didn’t come upon the history of Frontier Nursing Service by accident. I was inspired by Mary Breckinridge’s determination to help mothers and babies and also, by the strong, capable women who joined her in the mountains.

In this uncertain time of the COVID-19 pandemic, we can witness many healthcare heroes who are sacrificing to help their fellow humans. They know one person can make a difference, if not to every person, at least to the person in need in front of them.

An Appalachian Summer blurb:

After the market crash of 1929 sent the country’s economy into a downward spiral that led to the Great Depression, the last thing Piper Danson wants is to flaunt her family’s fortune while so many suffer. Although she reluctantly agrees to a debut

party at her parents’ insistence, she still craves a meaningful life over the emptiness of an advantageous marriage.

When an opportunity to volunteer with the Frontier Nursing Service arises, Piper jumps at the chance. But her spontaneous jaunt turns into something unexpected when she falls in love with more than just the breathtaking Appalachian Mountains.

Romance and adventure are in the Kentucky mountain air as Gabhart weaves a story of a woman yearning

for love but caught between two worlds—each promising something different.

For more information, visit Ann’s website.