Welcome Rosa! We’re excited to talk to you today about your fascinating memoir, DWELL TIME. First, what made you decide to write a memoir and share your story?

In 2009, when I had the Rome Prize at the American Academy in Rome, I came across the memoir The Periodic Table by Primo Levi. As I read the way he structured a family story around the metaphor of chemistry, I realized that I had a similar book in me, about conservation. Initially, I thought of it entirely as a way of showing the world what the conservation field is all about, because there are no books out there AT ALL that display our work in a way that is true and makes sense. Our profession is rife with powerful metaphors about damage and repair, and I felt that telling that story would resonate with so many people. I thought about this book for years and years but put it on the back burner as I built a business, which is now the U.S.’s largest woman-owned materials conservation practice. Then, the pandemic happened. Suddenly I found myself with time to write and reflect. I began a novel, hired a writing coach to help me structure it, and out of the blue I mentioned this idea for a memoir. She said, “stop everything and write that book proposal.” As I began to unpack the conservation material, a story about my family burbled through the narrative. It centered around my troubled, volatile, and extremely abandonment-averse mother. I realized that our family’s loss of Cuba, a country that my grandparents had moved to in the 1920s traumatized my family irrevocably and made my parents difficult to live with. As I wrote, I began to see the healing metaphor within this subject matter as a way to understand my family history of double exile. Art Conservation teaches us that the basis of all repair is understanding the source of damage. My goal with this memoir was to use this knowledge I have to unravel and learn to understand the intergenerational trauma at the foundation of our family life.

What is the definition of Dwell Time and why did you pick it as the title for your memoir?

In conservation, the term dwell time refers to the amount of contact time a chemical material needs to work. It is a measure of action on something you are trying to remove— soap on dirt, solvent on a stain, paint stripper on a varnish. The term dwell time also refers to the total time a person spends in an airport, or looking at a web page, or the time a family lingers at a border, waiting to get into a country, or the time you live in a city before moving on. I chose this title because it perfectly describes how I was trying to clean away the murkiness that made my family difficult to understand. Metaphorically, Dwell Time can also mean the amount of time you need to work on a problem. As I write in the book: We repair and make reparations by taking the risk of going past our own immediate emotions. Acting is its own salvation. You take the harsh decision or material, blend it into a gel, and watch the magic happen. The content of this book is like one of those solvent gels. That’s my hope, anyway.

What exactly is an art conservator and why did you pursue this career? How is it connected to your personal history?

Materials conservators (this term is more esoteric, but it’s used to include both art and architecture) repair, preserve, and perform preventive maintenance and basically enhance the longevity of all built heritage, which includes artworks, natural history collections, books, media, film, sculpture, paintings, murals, textiles, costumes, tapestries, archeological sites, and historic buildings and their materials. Our work blends art, science, and good hand skills. We are trained in the science of chemical deterioration and repair, and we work within specialties, like doctors. In public building restoration projects, for example, we are the ones who determine how stone or metals are treated, how terrazzo floors are repaired and salts leaching through tiles are addressed, yet we are often relegated to the sidelines and the architects get all the credit, even though they do not have the technical knowledge about materials that we have. In art, the curators, gallerists and fabricators get all the attention, yet it is only we (conservators) who know what to do when someone puts their elbow through a painting, or an outdoor sculpture starts to rust. I pursued this career because I fell into it. I was studying art and not very good at it. A professor recommended the field to me. I got into grad school by default and found that the field dovetailed with my sensibilities. It was all a bit subconscious I imagine. As a conservator, you are a servant to a work of art, never the protagonist. It’s got an odd humility to it, work done in the service of someone else’s aesthetic. I was raised to be beholden to others’ visions, my mother especially.

You left Cuba when you were four years old and returned for the first time thirty years later to attend a preservation conference in Old Havana. What was the significance of this trip? How is Cuba so closely aligned with your work?

The significance was monumental. My entire life shifted. I began going to Cuba as often as possible. It was all I wanted to do. Seeing the extraordinary historic fabric of Havana and Cuba- the amazing materials, all needing repair-was a seismic shift in my attention. I was trained to do exactly what Cuba needed. And, I had never known anything about the historic buildings there – the 500 continuous years of architectural history in tile, stone, metal and wood. 99% of Cuba’s buildings are historic and every single one needs work. And yet… the embargo and the U.S. relations with Cuba make it impossible for me to work there.

You write in your memoir, “Being a Cuban exile made me into a hyper-outsider, someone separated from the others by a steel trap door of misunderstanding born of the political situation.” Please explain.

Cuba and the U.S. are sworn enemies and Cuban Americans are the reason for this sixdecades-long embargo. It’s all about Florida politics. Florida is a big swing state, and hardline B.S. about Cuba being a terrorist nation, etc., wins votes from the strong Cuban voting bloc. The U.S. has relations with Vietnam and China, but not Cuba. It makes no sense. When the Soviet Union controlled Cuba, travel by Americans, especially Cuban Americans, was highly restricted. When the Soviet Union fell, and Americans, including Cuban exiles began traveling there in more significant numbers. We were like hyper outsiders because we knew so little about the country compared to other Latin Americans, who had been going back and forth with ease. It is an odd situation that all immigrants from communist regimes understand.

DWELL TIME focuses on your relationship with your mother. Describe the impact immigrating from Eastern Europe to Cuba had on your mother, how her trauma was passed down to you and ultimately shaped your relationship with her.

My mother and father were born in Cuba. Their parents were the Eastern Europeans who came to Cuba. My parents thought of themselves as 100% Cuban, but also Jewish. My mother’s trauma comes from her abandonment and losing her mother at birth. She was partially raised in an orphanage. I believe she has a personality disorder born of trauma, like Borderline Personality Disorder. I don’t name it in the book because I’m not a psychologist. She was very poor growing up. She married my father in part because of his stable financial life. They fell in love later. When the Cuban revolution happened, and they lost everything, she was re-traumatized. She was always anxious, angry, nervous. And in the U.S., she took all of this out on me. She was, quite frankly, abusive. I don’t use that word either in the book because it’s facile and also because she is alive, and I don’t want to hurt her. My father’s father was similar in temperament to her, and he remained stuck in a pattern with her, unable to leave her, and I was actually deeply grateful that he never did, because if he abandoned her, life would have been a true living hell. That said, my mother is extraordinarily loving, brilliant, cunning as hell, hilariously funny, but she has a virulent dark side and can turn on a dime. I walked on eggshells my entire life. I still do. Less so, but still. Writing has helped me heal a lot.

You write in your memoir, “Mistakes are devastating to conservators. We rarely talk about them. Failure is not built into our practice.” Explain what you mean both professionally and personally.

Think of doctors. They’re trained to heal patients, not hurt or kill them; however, everyone makes mistakes eventually. You prescribe the wrong medicine, you fail to see a contraindicator. In our field it is a similar practice. Your hand slips with the scalpel and a marble sculpture gets scratched. Or a piece falls off your worktable and breaks, or a material looks like one thing and it’s actually another. That’s what I write about- a pigment that looked like one thing but was something else, which led to it falling off during treatment. As a person, I hate failure also, but who doesn’t? But conservation teaches me that we are always balancing how far we go with anything. I failed at two partnerships, one close work relationship and one marriage. And I have bounced back from all of them, in part, by recognizing where I was responsible. In the book, I focus on my own complicity in the failures that affected me. It’s always easy to blame someone else, but owning failure is incredibly empowering. Our field is scared of it, I think.

What was your biggest success in your career? Your biggest failure?

My biggest success was building RLA Conservation, the firm I founded and currently work for, into the largest woman-owned firm in the U.S., making it also one of the most diverse firms in the U.S., and then having a new generation of owners who want to keep it going. We’re known nationwide for our excellence and as a great place to work. I love having built that. And of course, we’ve worked on many, many cool projects for historic buildings and artworks, like the mosaic on the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, The Watts Towers, works by Damien Hirst, Donald Judd, Roy Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg, and art by every major sculptor of the modern era. Failures… I write about one damage to an artwork. I also was unsuccessful at treating other things here and there. And of course, failing at work relationships. In my early years, I was an anxious boss, yelling at people, always stressed. I see that as a failure, but from that failure and others like it, I learned to mend myself.

You write towards the end of DWELL TIME, “Our people, nuestra gente Cuban and Jewish alike, did not abandon our parents.” Please explain.

In some ways it’s a generalization, but I was taught that Cubans, Latinos, Jews… we are all family oriented. We don’t abandon our parents, even when they are difficult. We may put in distance if wellbeing calls for it, but we try to remain present. To do that, one has to be mindful and patient. Some people sublimate their own desires to care for their parent, but understanding their brokenness makes it not only easy but also a source of growth.

What do you hope readers will take away from your memoir?

Courage and optimism. Damage is inevitable, but repair is always possible. Human beings are natural repairers. And things (objects, relationships) that are mended can be dearer than those that were never broken. Love is a phenomenal adhesive. One has to learn how to use it properly, but if we begin to understand the exhilarating possibility of restoration, we can deal with each other with gentleness, with care, and as beautiful, bruised creatures that deserve tenderness. I hope that this memoir opens dialogues about community repair and reparations as well as personal action.

Thank you so much for joining us today, Rosa!

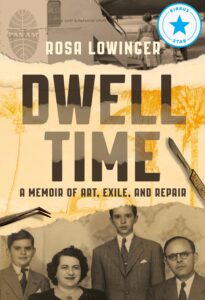

Readers, DWELL TIME: A Memoir of Art, Exile, and Repair, is available for pre-order. Here’s a quick look.

Dwell Time is a term that measures the amount of time something takes to happen – immigrants waiting at a border, human eyes on a website, the minutes people wait in an airport, and, in art conservation, the time it takes for a chemical to react with a material.

Dwell Time is a term that measures the amount of time something takes to happen – immigrants waiting at a border, human eyes on a website, the minutes people wait in an airport, and, in art conservation, the time it takes for a chemical to react with a material.

Renowned art conservator Rosa Lowinger spent a difficult childhood in Miami among people whose losses in the Cuban revolution, and earlier by the decimation of family in the Holocaust, clouded all family life.

After moving away to escape the “cloying exile’s nostalgia,” Lowinger discovered the unique field of art conservation, which led her to work in Tel Aviv, Philadelphia, Rome, Los Angeles, Honolulu, Charleston, Marfa, South Dakota, and Port-Au-Prince. Eventually returning to Havana for work, Lowinger suddenly finds herself embarking on a remarkable journey of family repair that begins, as it does in conservation, with an understanding of the origins of damage.

Inspired by and structured similarly to Primo Levi’s The Periodic Table, this first memoir by a working art conservator is organized by chapters based on the materials Lowinger handles in her thriving private practice – Marble, Limestone, Bronze, Ceramics, Concrete, Silver, Wood, Mosaic, Paint, Aluminum, Terrazzo, Steel, Glass and Plastics. Lowinger offers insider accounts of conservation that form the backbone of her immigrant family’s story of healing that beautifully juxtaposes repair of the material with repair of the personal. Through Lowinger’s relentless clear-eyed efforts to be the best practitioner possible while squarely facing her fraught personal and work relationships, she comes to terms with her identity as Cuban and Jewish, American and Latinx.

Dwell Time is an immigrant’s story seen through an entirely new lens, that which connects the material to the personal and helps us see what is possible when one opens one’s heart to another person’s wounds.

From the book: “How, I wondered, was it possible that no one in my family had ever told me that Havana, the place where we were from, was so closely aligned to my work? More importantly, how had I managed to reencounter this ornately decorated, sagging city at the precise moment when I was beginning to see a link between restoration of the material world and personal healing?”