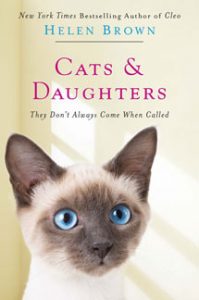

Helen Brown is the award-winning, bestselling author of Cleo, and has just released to critical acclaim, Cats & Daughters, They Don’t Always Come When They are Called.

Q: You believe rather curiously that cats step into people’s lives with a purpose, like when Cleo came into your life all those years ago. What did Cleo bring to your family during the 24 years she lived with you?

Well, she brought a great deal of healing. I wasn’t expecting anything to happen. In fact, I grew up in rural New Zealand where cats were treated basically as rat catchers who had no dignity or anything like that, so I think I was pretty prejudiced. This little kitten came into our lives very soon after our son Sam had been run over and killed at the age of nine. Sam had actually ordered the kitten three weeks before he died and we were all so traumatized that I’d forgotten it. When the friend appeared on the doorstep with this kitten, ready to give it to us, I just wanted to send it back because it was another living thing to look after. It was the last thing I felt capable of, but Sam’s younger brother Rob, who’d seen the accident saw this little kitten. He said, “Oh, Mum, it’s Sam’s little kitten, Cleo. Welcome home, Cleo.” And that’s the first time I’d seen Rob smile since the accident. He was only six. He gathered this little bundle up in his arms. It was the beginning of how Cleo started to help us.

She stayed with us for over 20 years and was like a guardian, in the end, just standing over us, watching—particularly over Rob. Sometimes I think she stayed with us for as long as she thought Rob needed her. Rob had his eye on this young woman for many years, and when she finally agreed to marry him, it was around that time that Cleo moved on to cat heaven or wherever it is that cats go to.

Q. It was a neighbor who said to you that your old cat chooses your new cat for you. You’d sworn you’d never get another cat despite the great love you had for Cleo. But as your mother always says, “It never pays to swear.” Curiously, your next cat arrived at another deeply turbulent time in your life, didn’t it?

Yes, he did. When I was halfway through writing the book about Cleo, I was diagnosed with breast cancer. I’d just had a normal mammogram, and suddenly it seemed I had quite a large growth—nearly seven centimeters. I needed a mastectomy.

After I came out of the hospital, my sister Mary flew across New Zealand to help nurse me. She went for a walk one day and said, “The only reason I’m going to tell you this is because you swore you’d never get another cat, but I just went past the pet shop and there’s an incredibly cute Siamese kitten in there.”

Of course, before I knew it I was bundled up in the car, clutching my stitches. We took Lydia, my older daughter, who was also causing a few problems at the time for me. We were peering at the little kittens, and there was this one gorgeous clown of a kitten who was leaping across the cage. He was using another little brown kitten as a trampoline, bouncing up in the air, scrambling up the wire. He climbed right up to my face and put his paw through the wire and stared up at me with these huge blue eyes…and I was his.

Q: You mentioned Lydia, your eldest daughter. She was quite independent, even as a toddler. She emphatically refused to call you “Mum,” even.

Yes, and I found that a little disconcerting, but in the end, I accepted it. At the age of five, she decided to become a vegetarian, with no encouragement from me. She once asked where meat came from and that was that. I had to lie. She’d say, “What’s in these sausages?” and I’d say, “Vegetables!” It was hard feeding one vegetarian and three or four carnivores.

Q: She was born into a grieving household, just two years after your son’s death, but she carried—and still does—an incredible sense of compassion into her teens. She volunteered to support severely disabled people.

I raised her and my other daughters to be very strong-minded, independent feminist-type women. And I always liked the idea of spirituality. I don’t belong to any religion but I’ve done my share of dolphin calling and bit of new age stuff…very open-minded. One day my yoga teacher said, “Look, we’ve got a Buddhist monk from Sri Lanka and he just needs a room to do a meditation session,” and I said, “Bring him to the house, we’ve got room.” Lydia was just eighteen at the time, and she sat at the back of the room while this monk led the session. It wasn’t until the end that I realized she’d been quite riveted by him, and at the end of the session, he flicked his beautiful maroon robes and beamed at her like a rock star. He said, “Lydia, you must come visit me at my monastery in Sri Lanka one day.” And I just sort of thought, Oh, that doesn’t mean anything. But my husband, Phillip, said, “I don’t like the look of that. I think he’s manipulating her.” I said, “Don’t be a silly old fuddy-duddy.” It wasn’t until she was in her twenties that I found out they’d been communicating for years, Lydia and the monk. She’d been helping him in lots of different ways, organizing retreats and things. I’d been a bit oblivious to this. It was around the time that I was diagnosed with breast cancer that she announced she was going to Sri Lanka with a view to become a Buddhist nun.

Q: How did you respond to that? Because she indeed went during the middle of your diagnosis, didn’t she?

Yes, and I must say I was shocked. But I was also incredibly hypocritical, because while I’d encouraged her to be spiritual, when she actually latched onto a religion with a view to taking it seriously, I was outraged. All the money I’d spent on her education and there she was going to sweep steps in a monastery! It was a pretty lowly life she was heading for as a nun.

Q: You were indignant. But there was a grief there, too. You were in a state of fear. Here you were, confronting your own mortality…

Yes, I was. I wasn’t sure what my diagnosis was at that point. But from the distance of time—it was four years ago, now—I see it so differently. I mean, if I had somehow turned her head around to make her stay in Australia while I had the surgery, she would have been so resentful, there would’ve been such tension in the air. It was actually the best thing possible that she took off.

Q: And you had to just let go?

It’s always like that. And it was always like that with Jonah, too. Between the two of them, that cat and that wonderful young woman, they have taught me to redefine love after thirty-five years or more of being a mother.

As a mother and pet owner, you often like to feel a degree of control. Even though you don’t use the word “ownership” in terms of your children, there’s some form of power. But there comes a point when you have to let go. It’s not letting go of the love. You don’t lose anything, ultimately. In fact, you gain a great deal, as I found with Lydia by actually letting her go to Sri Lanka. When she got there, this monk who I had this bit of a snitch on because he’d “stolen” my daughter, he’d refused to teach her. He had actually sent her back to Australia to help nurse me while I was recovering.

Q: She has an uncanny knack of chanting in all sorts of contexts in your life, doesn’t she? You emerged groggy from an operation, and there she was, chanting for you.

At first I thought I was hallucinating. It wasn’t until the nurse sort of chuckled and said, “Your daughter’s here.” She brought a bottle of holy water from the monastery, but the nurse said, “Just flush that down the drain.”

Q: Back to Jonah, the mischievous little animal that ended up on Prozac…what is it about pets that carry you through a time of grief or despair or fear?

It’s many things. I think the fact is that they’re always there. They’re constant. No matter how much you want other humans to be there all the time, no matter how hard they try, they can’t be. But pets are effortlessly there for you. A lot of the time when I was ill, I’d want Phillip to go back to work or the kids to get on with their own lives, because you don’t want to take too much from them. An animal just gives.

With cats, anyway, they have a psychic quality about them. They know when you’re suffering. Even now, Jonah loves it when someone gets sick in our house because he gets to nurse. He’d sort of snuggle up to the bits of me that were in pain and purr. They do say there’s physical healing in the purr of a cat, that it can lower blood pressure and all sorts of things.

Transcribed and edited from Helen Brown’s interview on ABC Radio National’s Life Matters.