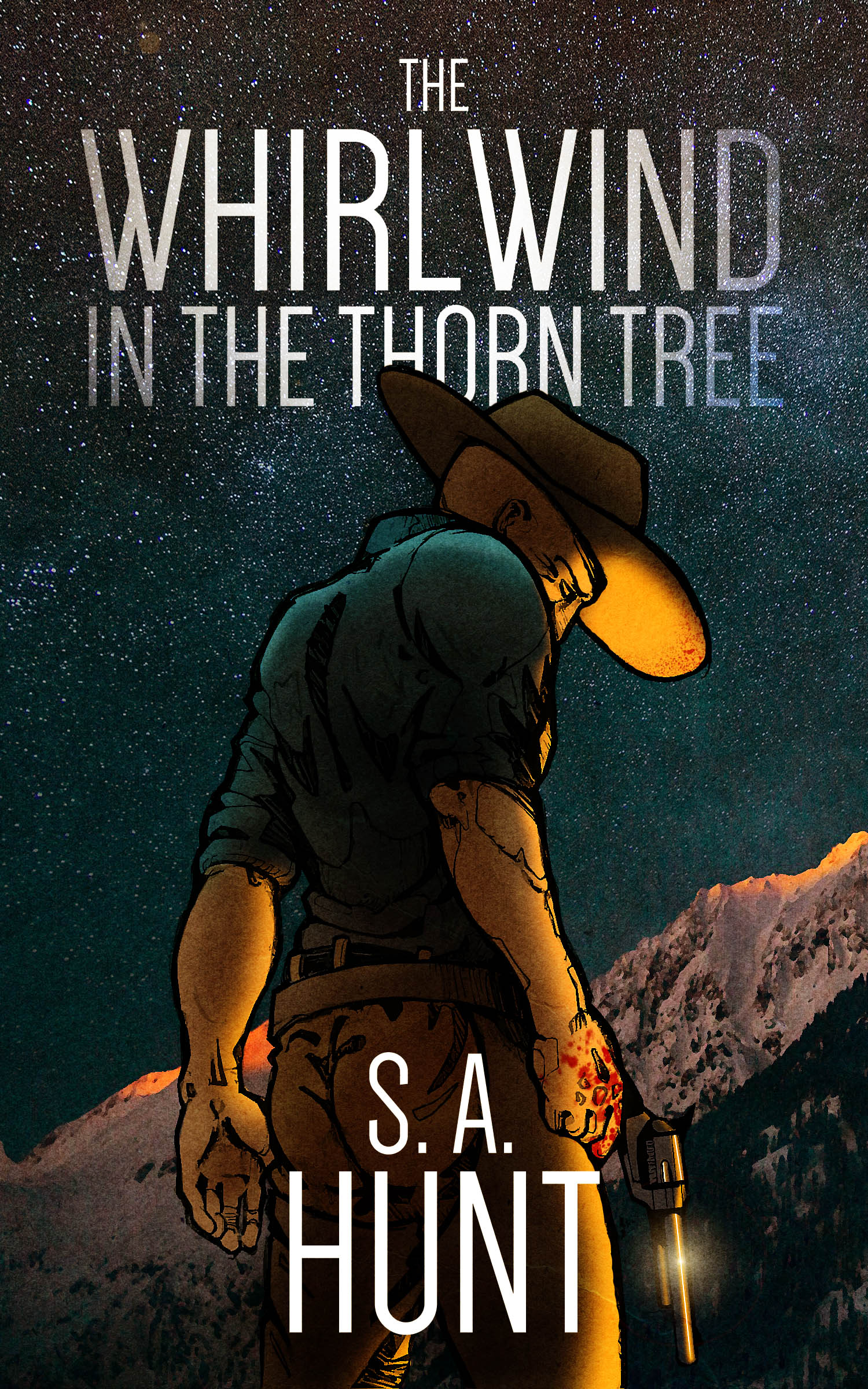

The Whirlwind in the Thorn Tree by S. A. Hunt

SYNOPSIS

The legendary gunslingers of late author Ed Brigham’s fantasy novels were supposed to be the stuff of fiction, but when his son Ross and two of the series’ fans stumble into the deserts of Ed’s fantasy world, they discover a war for the very soul of the universe, waged by the muses that once pledged to enrich it — and a strange secret that points to a deeper mystery that might involve America itself.

Inspired by such wainscot and portal classics as Stephen King’s The Dark Tower, Neil Gaiman’s American Gods, C. S. Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia, and Madeleine L’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time, The Whirlwind in the Thorn Tree is the visionary beginning of a series that will dive into the metaphysical center of what it means to create…and what it means to destroy. Join our protagonists as they go from modern-day Earth to the sands of an exotic parallel world, where a climactic battle will take place on the shores of consciousness…and challenge the rules of the written word itself.

EXCERPT

My Ithaca

I AWOKE TO THE LIGHTS of home, jostled from sleep by the Greyhound bus as we rattled down an offramp. I peeled my face away from the windowsill and sat up, pulling the fleece cap off my eyes and looking around. Lexington scrolled past the glass, greeting me with an urban smile I hadn’t seen in a year.

I tugged the hat down over my eyes again and savored the feel of the tires grumbling on familiar surface streets.

The bus pulled into a parking lot, waking me up again. I grabbed my backpack and sidled off into the cool night air. The driver opened the sidewall compartments and helped me pull my bags off onto the asphalt: a black gym bag, a green canvas duffel bag, and a camouflage rucksack, all of them stuffed to capacity.

He grunted as he dragged the rucksack out and it hit the ground with a soft thud. I caught a glimpse of the tag the airport baggage handlers had put on it. It was a picture of a stick figure bending over with a lightning zigzag coming out of his back, and the words “TWO MAN LIFT”.

“There we go,” he said. “Gonna be alright? Got somebody to pick you up?”

“Yeah,” I said.

He hesitated for a moment, wiping his hands on his pants, glanced at me, then got back on the bus and started writing on a clipboard. I took off my backpack, then knelt and hoisted up the rucksack, shrugging into the complex strap frame. I put my backpack on my chest, then squatted to pick up the gym bag and duffel, and shuffled away.

I felt like an astronaut in my rucksack and heavy boots, just returned from a journey to an alien planet.

I made it across the parking lot of the pizzeria next door and was halfway across the next when I had to put the bag and duffel down and rest. Cars shushed past on the four-lane, oblivious white-eyed roaches scurrying back to whatever hidey-hole they lived in.

I panted, my breath a billow of white in the late fall air, and listened to the droning buzz of the sodium mast-light overhead. Exhausted by almost a week of constant travel, I was starting to sweat in my uniform.

I hefted my stuff again and resumed my shuffling quest.

The stark lights of the restaurant were a welcome sight. It wasn’t too busy; there were a couple of families eating supper, kids playing in the enclosed jungle gym, a young couple in a corner booth. An old guy in a threadbare jacket was standing at the front counter.

I squeezed in through a side entrance and crammed the duffel, gym bag, and backpack into a booth and sat down next to my rucksack. My crap and I had pretty much occupied an entire booth.

Once I’d caught my breath, I took out my cellphone and turned it on. I dialed Tianna’s number and put it to my ear.

“Hello? Ross?”

“Hey,” I said. The plastic bench felt slick and strange against my fatigues. “Yeah, it’s me. I’m home.”

“Where are you?”

“The Burger Queen on New Circle Road.”

“Okay,” said the voice on the other end of the line. “I’ll be there in a minute.”

I hung up the phone and went to the counter to order something to eat, feeling self-conscious in my rumpled regalia. I could feel eyes on my back as I waited for my food, unconsciously toying with the wedding band hanging from the chain around my neck. The world around me felt unreal, an elaborate prank.

I sat back down with my boothful of fat traveling companions and dug into my cheeseburger and fries.

I thought it would be an orgasmic experience after so long eating NATO chow like raw cabbage, beat-up fruit, and rabbit stew, but it tasted…grungy, for lack of a better word. Dirty, greasy, heavy. It tasted like the junk food it always was.

My first meal at home was a distant memory by the time I saw the pickup truck pull into the parking lot an hour later. I got up and reassembled my astronaut getup, then carried it all outside to where the Dodge sat, idling.

My wife got out and watched me load all my stuff into the back.

“Hi,” she said.

“Hi.”

We stood there for a long moment, and she stepped forward and we hugged. I wish I could tell you that it was a passionate reunion like the movies, with lots of feverish pawing and kisses, but I’d be lying to you, and I don’t quite want to get into tall tales just yet. There will be plenty of unbelievable things recounted later, believe me.

The embrace, brief and stiff, broke off and she stepped back. She gave me a vague, wistful smile through the hair the wind was blowing across her face.

I tucked it behind her ear and she said something I couldn’t quite hear. “Hmm?” I asked.

“I said, I missed you.”

“I missed you too.”

She got into the truck. I slid into the passenger seat and rubbed my hands together, savoring the blast of hot air from the heater vent. We pulled out of the parking lot and merged with traffic, my hands warming on the dash.

The silence was uncomfortable, but I didn’t have enough time to get wound up over it and turn on the radio, because our house was only a few minutes’ drive away. We climbed a steep curve, slipping through the looming oaks of the neighborhood night like a snake through a tunnel. The headlights washed up the driveway and over the front of our home, a sprawling 1970s ranch house.

My teeth started to hurt and I realized my jaw was tight. We pulled up into the carport behind my Mercury Topaz and Tianna put the truck into gear. I got out and took my stuff out of the back, carrying it inside.

I loved that house…the groovy-dude architectural taste made it into a work of Brady Bunch art. It was like a bargain bin Frank Lloyd Wright creation—the whole foyer was visible through a floor-to-ceiling glass window with the front door in the middle of it. Not very secure, but for the rent we were paying, it was Beverly Hills on a Podunk budget.

Almost every wall had a window in it looking through to the next room, and was filled with either plate glass or shelves laden with knick-knacks—or, would have been, if the knick-knacks were still there. As I came in, I realized that the walls were bare and the closet in the foyer was empty.

I carried my stuff into the living room and saw that while my TV, recliner, and the shelf my mother had given us were still present and accounted for, everything else was missing: the sofa, all the pictures, tables, and lamps, the dresser that contained all the vinyl records for the turntable I’d bought her last Christmas, and the big mirror that had been hanging over it.

I went into the bedroom. The bed and dressers were gone. The closet was empty of everything but my own clothes.

The linen closet was empty and so was the bathroom medicine cabinet. I went into the kitchen and opened all the cupboards. The pots and pans were gone, the dishes, the blender, the Foreman were gone. My quesadilla maker was still there. The fridge had nothing in it but a bottle of margarita mix, a squirt-bottle of mustard, and a half-stick of butter.

I came back outside. She was standing next to the Dodge, which was still running.

“Do you have everything you need?” she asked. “I’ve got somebody waiting on me.”

I still don’t know if I was actually confused or just playing dumb. Perhaps I only asked what came out of my mouth next because I didn’t want to accept the truth.

“Everything I need?”

“Yes.” Even though her voice was low and soft, the silence of the fall evening made it easy to hear her.

I just stood there, as my mother was wont to say, ‘like a bump on a log’. I didn’t know what to say. I don’t know what I had expected, but it wasn’t this. It wasn’t an empty house. Concessions, maybe. Reconciliations, arguments, reassembly, repair, patchwork. Me sleeping on the couch for a while. Awkward breakfasts. Getting to know each other again. Apologies. Not using pet names for a while.

Not this.

I looked down at my feet, at the desert dust still ground into the rawhide of my boots. I wouldn’t need food. I wasn’t hungry. I wondered if I would ever be hungry again.

I sighed and said, “Yes.”

She opened the door, but didn’t get in. I was a deer in the headlights, literally and figuratively, on my feet in the washed-out white of the truck’s low-beams. I had enough time to think about asking her to stay, to think about asking her why she wasn’t staying, to ask her where the dog was. Our dog was not in the house, not in our house, the dog was not home. Where was the freaking dog?

I opened my mouth to speak, but didn’t. She stepped up into the truck and sat behind the wheel.

A few minutes later, my wife closed the door, put the Dodge in gear and backed out of the driveway into the street, slowly put it in drive, and drove away.

I remained there in the dark, a shadow and piece of the night, standing next to my car listening to the distant sounds of the city.

When I got tired of being cold, I went into the house and turned the heat on, then went into the living room and sat in the recliner. The acrid smell of burning dust from an unused heating unit filled the house.

I looked up and saw the blinds over the living room’s big picture window. I had put them up on my mid-tour break seven months ago, when we had moved into the house. It had been a massive pain in the ass but I’d done it for her—they were too big and I had to redo the brackets several times, but I had been happy to do it. I was happy and looking forward to coming home for good.

Home. It was my home. My house. My name was on the lease and the address was on my Army paperwork. I was paying the rent. But I had never lived in it.

I sat in my armchair looking at the lights of the city, ignoring the stink of baking dust.

After a while—maybe an hour, maybe three hours, I’m not sure—I got up and stood in the middle of the living room for a bit, my mind beginning to whirl. My eyes had become adjusted to the darkness, turning the house into a monochrome labyrinth, a mausoleum wallpapered in dingy yellow.

I sniffed. Looking down, I saw the shelf.

My mother had given it to us as a house-warming gift, a five-tiered curio shelf about four feet tall. It was made out of particle-board with a wood-grain veneer, and as fragile as a carton of eggs. Our wedding photos used to stand on it, in a large frame that was made to look like an open book. It also once displayed two music boxes and a backless clock inside a bell jar.

I picked it up, carried it out onto the carport, and slammed it against the cement floor with everything I could muster. It exploded into six pieces. I picked up the biggest piece, a half-shelf with a leg sticking out of it, and used it to club the rest of the debris. A chunk of the board broke, bounced off my face, and twirled into the darkness. I ignored it. The end of the leg broke off and hit the ceiling.

I threw the piece of wood in my hand and stood shivering with rage, trying to think of something else I could break. The laundry room was immediately to my left through an exterior door. I opened it and turned the light on.

I was looking into a small space with a washer and dryer inside and garden—no, the gardening tools were gone. That was probably a good thing: we had a “Garden Weasel” that consisted of a long handle with three spiky rotors on the end of it and looked like some sort of medieval death-hammer.

The washer and dryer were coin-operated; our last landlord had given them to us when he replaced the machines in the apartment complex’s open laundry. I’d had to pry the quarter boxes out—and to use them, you had to reach down into the mangled timer’s housing and pull a lever. An inconvenience, but worth it for a tough, high-capacity machine.

As I went to close the door, I saw something written on the wall in pencil.

It was very small and gave me chills every single time I saw it. We had discovered it the day we moved in, as we were installing the dryer. At the time, we called it our ‘good luck charm’.

Someone who had once lived here had scrawled, This was a very happy home. 11/26/88

My throat closed up and I held the top of the dryer like a little kid on a boogie board because I could feel it coming. I knew it was there lurking in the dark, cold house, when I saw the blinds. But when I quite literally saw the writing on the wall, I felt the top of my heart crack—and as I slouched there gripping the dryer for dear life, the entire thing broke into a thousand pieces.

_______

I was still sitting in the recliner when the first rays of Kentucky sunlight came over the trees, golden spears tracing long arcs across the wall and kitchen door, solid and heavy with snowlike dust. My right knee was bouncing and my eyes were raw and grainy.

My cellphone rang. The opening bells of Ray LaMontagne’s “Gossip in the Grain”, tinny but always beautiful, resonated in the morning stillness. Ding ding ding…ding …ding.

It rang again. My hand came up off the chair’s arm and I wiped my wet nose with a paper towel, a piece of Bounty, because there was no toilet paper.

Ding ding ding…ding…ding.

I picked it up and looked at the screen as it rang again, in my hand. The digital readout told me it was 7:12 AM. I pressed the Call button and put it against my ear.

I could hear someone breathing. I finally said in a listless voice, “Hello.”

“Ross?” It was my mother Caroline in Georgia. “Are you home yet?”

I swallowed and tried to speak. My vocal chords didn’t kick in at first, and I had to stretch the word out.

“—Yes.”

“Are you there? Hello?”

“Yes,” I said, “I’m home. I got home…last night.”

“Oh,” said my mother. “I’m so sorry. I’m so sorry.”

I blinked. How did she know? I sat up, slowly, like a mummy rising out of the sarcophagus, and huddled on the edge of my seat, hugging myself with the phone against my head. “What about?”

“Your dad.”

“My dad?” I asked. Like my voice, my thoughts seemed to be coming to me from some faraway place, as if I were listening to them on a shortwave radio. I felt as if I were on the airless moon, thousands of miles away from everything and everybody. I breathed, watching the motes of dust orbit my face. “What about my dad?”

This wasn’t about the first shoe. This was the second shoe dropping.

My mother sighed. Her voice was slow and measured and sympathetic. “He…I’m so sorry you had to come home to this, son. I’m so sorry. He had a heart attack yesterday. He was…. Ed’s gone. Eddie’s gone. His agent Max found him.”

I listened to the birds outside. I hated them. “Goddamn,” I said.

My mother didn’t respond, but I could feel her confusion.

“She left me,” I said, looking at the floor. “All her stuff was gone when I got home. She’s gone too.”

“Ohh, son. I’m sorry. There’s—there’s not really anything I can tell you that’ll make you feel better. Maybe it’s better this way, baby. Maybe you’re better off.”

Knowing someone was listening to me ruptured whatever control I had developed during the night. I started sobbing. She listened to me as I struggled to maintain myself. When I had settled enough to listen, she spoke.

“Why don’t you come home? Get out of that empty house for a little while and come to the funeral. They’re doing it in a couple of days. I hear there’s going to be a few of his fans there. It’ll be good for you, you’ll have somebody to talk to. You won’t be alone.”

I said, “Okay.”

After I got off the phone with her, I took a dose of melatonin, swung out the chair’s footrest, and took a nap for a few hours. When I woke up, I put a couple of outfits in my backpack with my laptop and left. If I’d known then what I know now, I would have taken all my clothes, because that was the last time I ever stepped foot in that house.

Cats, Cradles, and Comic-Cons

I WAS STANDING IN MY SHITTY HOTEL ROOM alone, adjusting my tie when it hit me that I was about to go to my father’s funeral. I suppose like any child, I must have assumed he was going to live forever.

In a way, he will, I suppose. They say that the only immortality that can be achieved by mortal man is through the act of creation. My father managed to accomplish both of these feats in his lifetime.

I finished straightening myself and left. My junky little car took some coaxing to start, but purred like a garbage disposal when I got it running. I pulled out of my parking space and took off across town, driving a little slower than usual. I wasn’t looking forward to my destination, and that had little to do with seeing my father dead in a box.

Speaking of my father, I’d like to introduce you to Vincent Edward Richard Brigham.

Yes, that’s four names. Born in June of the year of our Lord 1951, Ed survived your usual Southern childhood: church every Sunday and fatback ham with turnip greens and black-eyed peas on a regular basis.

In high school, he started tinkering with the medium of fiction, and in the middle of his first year of law school, Ed discovered what he was meant to do and then he did the impossible: he started making a living writing fantasy novels south of the Mason-Dixon line. As you can imagine, passing the bar was no longer of any concern.

Over the next forty years, my dad made a name for himself in the hearts and minds of bookworms everywhere with his novel series The Fiddle and the Fire, a fictional biography of a man’s life in pursuit of vengeance across a fantasy-western world.

We lost track of each other somewhere between that second and third decade, so to speak, but he went on to become a semi-legend in the entertainment world…not exactly a name on the lips or scripts of Katie Couric or Mary Hart, but whispered to each other over dusty paperbacks at the neighborhood book shop and doggedly tracked down on Amazon. He was like the American god that he turned out to be, ubiquitous but invisible.

I barely registered the drive to the chapel and before I knew it, I was there. Unfortunately, I was nowhere near as invisible as Ed used to be.

The teenager at the podium, who had just given his own personal eulogy, was wearing a polished revolver like the ones from my dad’s books. I hoped that the gun wasn’t real, as he stepped down from the podium at the front of the funeral party and returned to his seat.

Following him back to his pew, I locked eyes with a pretty girl a few rows back, on the other side of the room. Her big, bright eyes, platinum-blonde hair, and serene expression made her look like a rock-chick version of a young Joanne Woodward. She waved daintily at me with a hand clad in a fingerless black glove.

I looked away. A heavyset girl dressed like a cross between Annie Oakley and a valkyrie stepped up to the podium, and gave her name as Judith Raske. She began to give a very sincere, heartfelt eulogy that I couldn’t quite pay attention to.

The man in the casket had no blood relation to anyone in the funeral parlor except for me. I sat in the back, wedged into a narrow space somewhere between schadenfreude and disappointment. I knew that Ed had managed to squeeze out enough of his fantasy series to amass a cult following, but none of us had expected to see almost two hundred people crammed into this tiny chapel.

The mourners considered themselves members of an extended family to three-time Hugo Award nominee Ed Brigham, the deceased fantasy novelist now resting on the dais at the head of the room.

I couldn’t believe I felt like an interloper at my own father’s funeral.

Most of them had the good sense to show up in their Sunday finest, but many of them wore ratty jeans and T-shirts with ancient, unintelligible decals peeling off of them. Those people who had the money, the guts, and the knowhow to craft quasi-medieval costumes were inspired by the finery my father had described in his book series. They were resplendent in their hand-crafted chain mail, their wide-brimmed hats, their leather long-coats and rich red tabards.

To my right, beyond my mother, was a churlish-looking, shaven-headed buffalo in biker leathers (LIVE TO RIDE, RIDE TO LIVE). In front of me, a very attractive woman in a conservative business skirt. To my left, across the central aisle, was a crater-faced youth that looked like Scottish Death in a Dropkick Murphys T-shirt, a black kilt with tactical pockets, and black combat boots. I saw several older women that clustered together in their pew, looking for all the world like a genteel country knitting society.

I could see the waxy white bald head of my father’s literary agent Max Bayard where he sat in the front row, his impeccable suit the soulless gray color of an office carpet.

I tuned back into the proceedings just to catch the words I dreaded hearing.

“—And although our good friend E. R. Brigham is now in—ahh—a better place,” Judith Raske was saying, “—we were regrettably left without closure to his long-running fantasy series, The Fiddle and the Fire. For those of you that might be unfamiliar with it, this was a string of novels that followed their protagonist from his childhood as the boy Pack, growing up on his father’s plantation, through the massacre of his parents at the hands of the Redbird bandit Tem Lucas, and on into his adult life as the gunslinger Normand Kaliburn.

“The final novel Mr. Brigham began was The Gunslinger and the Giant, which went unfinished due to his sudden and unfortunate passing this year. It was to recount the Battle of Ostlyn, the outcome of the war, and the conclusion of Normand’s vendetta against Tem Lucas. It saddens all of us to see this long-told tale go uncompleted.”

I felt my heart quicken. Frozen mice scurried through my veins. Bayard looked over his shoulder at me, the windows glinting on his eyeglasses.

“I would like to take this opportunity to inform everyone assembled about—ahh—a petition that was started on the online Fiddle forums soon after this terrible news reached the internet fan community,” said Judith.

I was very aware of this petition; it was the source of my current anxiety. She adjusted her glasses, bumping the microphone with the Batman-style swordbreakers running down her bronze gauntlet. A muffled thud reverberated throughout the room. “Excuse me. It started slowly, but soon reached over twenty thousand signatures.”

If I was drinking something, I probably would have spewed it all over the person sitting in front of me.

“This petition began half in jest, according to the man who put it together, Sawyer Winton,” the girl said, then paused, squinting into the congregation. “Sawyer, could you come on up, please?”

Someone stood up behind me; I turned to see a slim young man in a sweater and cargo pants. His black hair curled rakishly over one piercing gray eye, and he had the scratchy beginnings of a handsome Jack Sparrow goatee. His healthy, clean-cut look gave me a sense of maturity that would give him conviction and purpose.

My father’s agent saw it too, and I expect he also saw the weird feathery quill that Sawyer was carrying, some sort of ridiculous ostrich-feather pen. He was also carrying a little camcorder, a GoPro. He was actually filming the funeral.

“You know what they’re gonna want,” Bayard had said on the phone. “What do you think about it?”

“I think I’m in big trouble,” I had replied, which was the absolute truth.

Winton stood beside the girl. To my alarm, his voice was confident. “Thank you, Judy.”

Judith continued. It struck me that she looked rather old to be wearing such an elaborate costume; she had to have been in her thirties or early forties. “But once it caught on, it burned like wildfire. What this petition requested was that continuing authorship of the Fire and Fiddle series be passed onto another writer, one particularly familiar with Mr. Brigham, as well as his style and subject matter. That writer would of course be Mr. Sidney Ross Brigham, his only son, a notable author and artist in his own right.”

I experienced something not unlike being sprayed in the face with gasoline mid-cigarette. As soon as her scripted speech finished, everyone turned to admire my now-crimson face. I managed to smile, although I suppose it might have more resembled the snarl of a cornered timber wolf.

“Mr. Brigham?” Judith indicated, and as I rose from my seat, I felt like a helium balloon slipping a toddler’s grip. I approached the podium through a chaos of applause, feeling a bit lightheaded, shaking their hands when I got there.

Sawyer leaned toward the podium, tugging the mike closer to his face. “We feel that your father would have wanted you to finish his magnum opus, and we as fans of his work hereby request authorship to be passed down to his son, so that the series can end on a proper note. Or, perhaps, even continue if need be.”

If need be? I was beginning to feel like a virgin sacrifice on his royal bamboo sedan being carried up the mountain to be offered to the tribal volcano god. Sawyer Winton held up the ostrich feather like a trophy goose and thrust it in my direction. I resisted the crazy urge to stick it in his throat like Nicholson’s Joker and accepted it, taking Judith’s place behind the mike.

As she turned to leave, her broadsword scabbard bumped one of the full-length candlesticks standing next to the casket and set it metronoming. I slid into place and grabbed the candle, settling it before it could fall over into the fake spray of flowers around Ed’s casket and start an open-casket cremation. I could just see the headlines in tomorrow’s paper.

“Hello, everybody,” I said, way too close to the microphone. My muffled voice erupted from the speakers flanking the dais. “First, I would like to thank you all for coming. From what I understand, my father loved all of his fans from the bottom of his heart and put every drop of blood, sweat, and tears he had into telling his stories for you guys.

“Second, I’m going to admit that I’m no good at public speaking whatsoever, and I have a very limited imagination, so in lieu of a visual aid to help me with my stage fright, I’m going to have to ask all of you to remove your clothing.”

No one laughed. My face felt like I’d been bobbing for ice cubes.

“I’ve actually been following the progress of the petition since not long after its inception,” I said, “—and I am deeply moved by your dedication to my father’s life’s work.”

I turned and glanced into the coffin behind me. My father lay face-up in the box, against his lifelong wishes, his hands pressed around the handle of a quicksilver broadsword, his eyes closed (thank the stars), dressed in an incongruous white robe. I realized with disconnected bemusement—and a vague horror—that he looked like Gandalf Lebowski, ready for entombment in the catacombs of a bowling alley.

I faced the crowd again, biting my lips to keep from laughing at my own imagination.

Ahh, the Inappropriate Laugh.

Most of them were looking at me with sympathy except for my mother, who I was glad had the restraint to keep from hurling her purse and sensible shoes across the room at my face. I took a second to gaze at the floor and compose myself again. “However, I regret that I must inform you: I was not remotely as familiar with his fantasy series as you, his eternal fans.

“Some of you may be aware that I was very young when my parents separated, and although he was awarded visitation custody, I did not see my father very much at all. Indeed, after a couple of years, my mother Caroline had to move up north for business, and I only saw my father Ed on holidays,” I said, staring down at the novel on the podium.

“Which I don’t suppose inconvenienced him very much, because after the move, the few times I ever spoke to him was when I sought him out myself. I’m not sure that he was aware of my birthday at all, nor did he acknowledge me on Christmas. Or Easter. Or Thanksgiving. Or Yom Kippur. Or even Kwanzaa. He didn’t even come to my Army graduation or come see me when I got home from deployment.”

The resentment made me brave. My voice seemed to carry farther than it had before, rolling out of me on wheels greased by bitter memories. “In fact, I’m not one-hundred-percent sure that my existence registered in Edward Brigham’s mind at all after 1986,” I said with a shallow sigh, opening the book. On the title page, my father had written To Judy Raske — To The Bounds of Behest and Beyond!

“So, I must admit that I may not be the most suitable replacement. I am deeply, deeply sorry that I must tell you that I have to decline the inheritance of E. R. Brigham’s series The Fiddle and The Fire.”

The entire gathering seemed to freeze in time, and each of the one hundred or more people I could see from the podium bore the expression of the proverbial “deer in the headlights”. I flinched at the sight of the near-instant transformation of the hundred-odd people before me from bereaved mourners to astounded lynch mob.

It’s also when I noticed the cameraman and his news correspondent standing next to him, standing in the back of the chapel, nestled in amongst the other attendees, ready and waiting to make sure the revolution would be televised.

The longer I studied their shock waiting for pitchforks and torches, the darker their faces got, until they were all murmuring to each other and glaring at me as if I’d changed the formula for Coca-Cola. This entire vignette, by the way, seemed to stretch on for three hours, but it in fact persisted a mere twenty-five seconds.

“Really?” asked Judith, her eyes wide and bright in the window-filtered afternoon sun.

“That—kinda sucks,” said Sawyer, and I watched the joy drain out of his face. The mild satisfaction I was feeling at cracking his boy-band confidence faltered, and the result of my insolence pierced me to my core.

“Look,” I said, sighing, “I apologize for the reaction, everybody. I really do. My father and I just really weren’t on the best of terms to put it mildly, and I don’t know a whole lot about his series. I read some of the first book when I was in the Army, but with work and everything over there, I never really got into it. And after that, well—I pretty much missed the boat, I think.”

Bayard got up and joined us on the dais. “We knew this was coming,” he whispered to me, cupping the microphone with one bear-paw hand, leaning into my face, filling my nostrils with his coffee breath.

I could see my own honey-colored cornered-wolf expression in the reflection of his 70’s bicolor glasses. It struck me that he looked like Hunter S. Thompson if Thompson was thirty pounds heavier and given to picking out ties to wear to Olive Garden.

“And you have no idea just how much this is going to blow up if you agree to step into your father’s shoes,” he was saying. “This could be the next big thing with this Comic-Con crowd. To that end, I’ve been working on a little something in my spare time. A little deal. Something to sweeten the pot.”

“What would that be?” I asked. “Max, you know I’m an artist first. I haven’t written anything worth a crap in ages other than that ghostwriter project, for the climber guy that got stuck in the Colorado mountains a couple years ago. I got a couple graphic novels and advertising jobs on the table.”

“HBO wanted to talk about doing a Fiddle TV series before your father passed. Nerf wants to license foam swords and dart revolvers. I’m even getting word of a video game. Of course, you would only see a fraction of it—but this all would make your residuals from Bear With Me look like hobo change.”

I felt a hand on my shoulder. It was Sawyer, and his eyes were like scalpel blades. “I’ve read some of your stuff, man. You’re not as bad as you think you are.”

I studied Bayard’s rubbery face and considered his intel, then stared down at the ostrich feather until the world around me faded to gray.

Once I’d had enough of pretending to think about it, I looked over to Sawyer and Judy, staring straight into Sawyer’s camcorder, and said loud enough for the microphone to catch, “You know, they say you can do anything if you put your mind to it. Let me sleep on it, okay? Let me catch up on the series, and I’ll see where we can go from there.”

They both grinned. A few people in the funeral party applauded softly. I scanned the people before me and saw quite a few more beaming faces than just a few minutes prior. Even the teenagers that looked like they woke up in a cave and came straight to the funeral were glowing.

Sawyer leaned into the mike and said, “We won the battle, guys. Here’s hoping we win the war!”

I smiled back at them. Their enthusiasm was infectious—I felt a little excited to be part of this. And then the enormity of the task before me came rushing back in a blast wave of fear.

Ravens and Writing Desks

AFTER THE VIEWING, I STOOD alone at the side of my father’s coffin, looking down at his aged body with a growing sense of sadness that threatened to eat at my edges. Conflicting emotions warred with each other.

Regret, at never bothering to get to know him better, at never closing that gap he created himself. Anger, at myself, for just writing him off as a reclusive hack. Anger at him for disappearing from my life until now. Satisfaction at having an opportunity for achieving something wonderful thrust onto me.

A cool, hollow void where a great weeping sorrow should have been at losing my father.

“I don’t think for a moment that talent is genetic,” I told the man in the coffin. “I’m no writer! At least not the kind of writer that twenty thousand people sign a petition over. I am definitely not my father’s son. What the hell am I going to do?”

My father said nothing, of course. The broadsword he clutched in his spotted hands gleamed bright, blinding bright, in the dusty light of the octagon window in the back wall where the slopes of the roof met. I turned around to what I thought was an empty viewing room and Bayard was standing there with his hands in the pockets of his suit jacket.

He stepped toward me and hugged me out of sympathy. I surprised myself by being grateful for it. He took off his rose-colored Thompson glasses and hung them by one stem from the collar of his shirt, and regarded me with ancient eyes. The ponderous bags under his watery hound-dog eyes made him look thirty years older.

“When I was a kid,” Bayard said, with a vague, wistful smile, “I came walking out of the town library and saw something big and black in the grass next to the sidewalk. I went to go see what it was and it turned out to be a raven, lying there on his back, looking up at me and cawing. I guess it got hit by a passing car and knocked onto the median.

“Well, that big dumb bird let me pick him up and carry him home. He had a busted wing and a broken leg. My dad, he was a doctor, he had a little clinic in Ohio, he helped me put splints on that raven.”

I smirked in spite of myself. “Does this story have a point?”

Bayard took a box of Camels out of his pocket and started packing them against the palm of his hand. “Walk outside with me.”

We hung out in the funeral home carport. Golden rays of sunlight filtered through the filthy washrag clouds and lit up the green leaves of the dogwoods flanking the driveway. The listless hiss and roar of oblivious traffic passing on the street down the hill was soothing in its detachment.

The literary agent lit a cigarette, took a deep draw, and blew the smoke across the carport in a thin stream. “A couple months later, that fat-assed raven was one hundred percent back to health. I didn’t want to, but my dad made me take him outside and let him go.

“No matter what I did, he absolutely would not leave. I shook the shit out of that dumb bird trying to get him off my arm. He knew he had a good thing and he didn’t want to leave. I took him out every day that week trying to let him go and he refused to do it.”

I gave him a Clint Eastwood squint from the corner of my eye and folded my arms. “Are you about to tell me that that bird never forgot how to fly and if I just believe in myself and quit resting on my laurels expecting the world to hand me a living, I can fly too?”

“A few days later he got ahold of my brother and tore him up, so my dad had to take him out and shoot him,” Bayard said, flicking his ashes onto the carport floor. “I’m telling you that if you don’t start flying, I’m going to shoot you.”

I laughed and he took a deadpan drag off the unfiltered Camel.

“Those things will kill you,” I said.

“World War II didn’t kill my dad, and neither did Camels, and if my wife couldn’t do it, this Camel ain’t gonna do it either.”

We stood there a minute, listening to the traffic. “I always wondered how Carl got that scar on his neck.”

“Well, now you know. So what are you gonna do, Ross?”

At that point, it hit me that over the course of my life, I’d probably seen more of this man than I had my own father. The idea stunned me. I managed to say, “Not sure. I guess write the damn book.”

“Attaboy. What made you change your mind?”

“Those people’s faces.”

“Very commendable. You sure it wasn’t the money?”

“No. Maybe that Winton guy’s right. Maybe I’m not so bad. Maybe I can do it. I don’t owe them anything, but…what kind of guy would I be if I didn’t even try?”

“It wasn’t the fame? Not even a little bit?”

“No. I just don’t—well, I guess I don’t really want to let them down after all.”

“You’re a damned liar.”

“Okay, okay,” I said, smirking at him. “Maybe the fame. Just a little bit.”

“Attaboy.”

_______

My mom, Bayard, and I were the last ones to leave—or at least I thought we were. On the way out, I passed the doorway into a little kitchenette and spotted Sawyer Winton sitting at the table inside, drinking a cup of coffee, his camera off and lying on the table.

As soon as he saw me, he spoke up, “Hey, Mr. Brigham!” and started to get out of his chair.

I told my companions I would be out in a minute and ducked into the little break room. “Don’t get up, Sawyer,” I said, settling into a chair myself. “And you can call me Ross.”

“Okay…Ross,” said Sawyer, sitting back down. But when he saw the expression on my face, he tensed up again. We sat there for a long moment like this, staring at each other. He pretended to fiddle with the camera, turning it on, and put it back down at an angle that captured both of us. No doubt some sort of documentation, experience footage, for YouTube.

At long last, Sawyer blurted, instead of whatever he had meant to discuss with me, “…What? What is it?”

“I’m a wee bit pissed,” I said. “What possessed you two to bring up the petition in the middle of my father’s viewing? Call me up in front of my dead dad and put me on the spot in front of my mother and God and everybody? That reporter? Did you both lose your minds? What the hell, dude.”

“Yeah,” he said, looking down at the table as he picked his fingernails. “I guess that wasn’t the most tactful thing to do, yeah, maybe. I guess I just thought something like that deserved some kind of—I don’t know, ceremonial feel, you know? A couple of the others thought it was kinda bad form, too. I’m sorry, Mr. Brigham.”

“Well…I know you meant well.”

I let the moment linger for emphasis, then added, “So what did you want to talk about?”

“I just wanted to thank you for considering the book, and to let you know that I’m always available if you have any questions about the lore and canon of the series. I’ve been a lifelong fan ever since I read the first book when I was in third grade. I’m gonna be in town a couple days visiting with a few of the other fans while I’m here.”

“Third grade, huh?” I said, taking out my cellphone. “What’s your cellphone number?”

As I entered his number into my contacts list, Sawyer said, “My teacher, Mrs. Kirby, was reading it, gave it to me when she was done with it. I finished it in like, a week or two, and she was so impressed and stuff that she went out and bought me my own copy of the second one as soon as it came out, later that year.”

“That’s cool.”

“Look, uhh…Ross,” said Sawyer, taking something out of his jacket. It was an elderly, dog-eared copy of my father’s second book, The Cape and The Castle. The pages were yellowed, the art on the paperback’s cover was faded by time and sun, gone green-blue. The picture of my father on the back depicted a much younger man, his hair and beard lush and dark.

“I…I know…you didn’t really have a good relationship with your dad. And I know you couldn’t give two damns about his novels. My dad died in a car accident and left me and my mother when I was seven, so I can understand, maybe. You just sit in your room and you think and think and think and you just wanna know—you just wanna know why, right?”

I studied my hands as they rested on the table in front of me, and glanced over at the accusatory eye of the GoPro camera.

“This series is what kept me company, man. You said you didn’t see much of your dad. Well, I never saw my dad ever again,” Sawyer said. “I would lie up at night reading your dad’s books until I got sleepy. Then for Christmas one year, my mom bought me the audiobook for the third book in the series. You know, the one Sam Elliott did in ‘95.

“At the time, I didn’t know who he was, so I pretended it was E. R. Brigham reading to me. Like…a bedtime story, I guess. It probably sounds weird, but in a way, I liked to think of him as a—as a sort of dad. Those times. Since I didn’t have one.”

When I looked up, Sawyer was gazing intently into my face. “That’s why I want this so bad. He did something very special for me, even if he didn’t know it. And I want to give back, y’know? I want to see his dream get finished. And after reading the stuff you’ve done—the autobiography about the dude in the mountains Bear With Me, the comic book you did a few years ago…I even caught the play in Chattanooga you cowrote with Marshall Davies right before you went into the Army.”

“Really?” I asked. I didn’t bother asking how he knew I’d been in the Army. Most readers knew at least the largest events of my life. “What were you doing in Chattanooga?”

“I was on my way home from college and my layover got cancelled. The snow.”

“Oh, right. That was a fun night.”

“Mm-hmm,” nodded Sawyer. “I actually went hoping your dad would be there, but no such luck.”

“Yeah, he didn’t get around to my things. He didn’t go to my graduation from Basic Training, either. Nobody did.”

“That sucks. I’m sorry, dude.”

“No big thing. What’s your email address?” He gave it to me and I entered it into my phone with his number. “This way if you need to send me large passages of text—or vice versa—you can,” I said, standing up. “Hey, I gotta go. Gotta catch up with my mom. Talk to you later.”

“Yeah,” Sawyer said. He picked up the camera, but didn’t turn it off.

When I got outside, everybody was already in the car, my mother driving, the Pontiac idling. They were listening to the latest pop music fad song on the radio, at such a low volume I didn’t realize there was anything playing until I walked up and leaned on the window. The car was spotless but still smelled of the agent’s cigarettes.

Bayard glanced at me over his shoulder. “Hey kid, you gonna be in town for a while?”

“Yep. I want to look through my dad’s working notes and take a look at some of his old haunts. See if anything inspires me.”

“That sounds like a good idea. I’ll be heading back to California in the next day or two myself.”

The clouds were darkening again, threatening the green birches and pines of Blackfield with warm, dirty rain as they danced their swaying tango, flickering paler shades of money green in the cooling September breeze.

“Thank you for doing the right thing,” she said, tucking a lock of her graying, once-auburn hair behind her ear. “Agreeing to at least attempt the book really made all the difference. I was back there and heard the sweetest things they were saying to each other about you. They’re all excited, son.”

“Kid, if it makes a difference, I can send out one of my other guys to help you. I’m sure one of them will be more than happy to collaborate on the final Fiddle book,” said Bayard.

I was beginning to feel introspective and morose. If this was a movie, I’m sure the poignant, haunting, minimalist piano score would have started playing around the time I had walked up to the car.

“No,” I said, “I think this is something I have to do on my own. My dad did it alone.”

All alone, I thought, gazing out at the scenery, the aging country storefronts, the gas stations, the mom-and-pop restaurants, the dead and dying commercial vestiges of yesteryear—drugstores, craft knick-knack shops, local-owned department stores—and seeing none of it.

_______

I sat in my motel room, watching the darkness gather between the curtains, until the only light I could see by was the ferocious glow of my laptop screen. I felt as if I were floating in a black void without end or beginning, my last remaining anchor the blinding empty-white rectangle in front of me, like some window in the wall of reality that opened onto the featureless wasteland of my brain. I wanted to reach through, pull the words out by the neck, and shake them until a story came out.

I turned on the lamp. On the table next to the laptop was one of three boxes of my father’s notes on the Fiddle series.

I had been looking through them in the hour since I’d gotten back from the funeral, but nothing was registering. All I could think of was the sight of my father in the coffin and how old he’d looked. That was the point in which it had struck me just how long it had been since I’d seen him last.

I’d never even gotten the chance to say goodbye, and what dug even deeper than that was the epiphany that until now, I had always had the opportunity, I hadn’t cared about taking it.

“Why didn’t you call?” I asked the box.

I got up and went out, putting on my shoes as I fled the question.

_______

A few minutes’ walk from the motel was a burger joint named Jackson’s, staffed by local college kids. Blackfield is a school town, so just about everywhere you went your transactions were handled by children, the vast majority of them as slender and attractive as the cast of your average cable TV teen drama. It was like living in Neverland.

When I walked in (pulling open a door that had a baseball bat for a handle), it felt as if I’d walked into some sort of cave overgrown with a strange green fungus.

Once my eyes acclimated to the dim interior of the dive, I realized that the walls and ceiling were wallpapered with dollar bills. They were taped, glued, and stapled to every structural surface in eyesight, and signed with everything from Sharpies to ink pens.

I took a booth in the very back of the L-shaped restaurant, by the restroom, out of sight of both the front door and the bar, where a television was touting a football game at top volume. After a few minutes of ogling the dollars on the walls and wondering what the insurance policy on the place could possibly be, a waitress approached me and took my order.

As soon as she left, I opened my laptop on the table and stared at the blank word processor. The icon in the corner told me that there was wireless internet coming from somewhere, and lo and behold, it was unlocked. According to the name—”Cap’n Pacino’s”—it belonged to the coffee shop two doors down. I logged on and busied myself reading the news.

The media’s half-assed coverage of the funeral was on a few lesser-known aggregators and social news sites. Fark, with a “Sad” tag and a comments section full of thugs and geeks flinging epithets and threats at each other. Reddit’s literature communities.

They were replete with apoplectic debates over the quality of The Fire and the Fiddle and comparisons with Tolkien, Saberhagen, King’s Dark Tower series, G. R. R. Martin, outrage at my outrage, outrage at my initial refusal to pick up my father’s mantle and please the masses, threats and promises to murder me outright both if I did and if I didn’t continue the series.

I ordered a hamburger, but I don’t remember eating it.

AUTHOR BIO

S. A. is

a U.S. veteran with very little money and far too much free time, which is now spent telling lies about time-bending cowboys.

You know

him

on Twitter as @authorsahunt and on the mean streets as Esé.

He lives in Georgia, US with a wide range of dangerous wildlife.

Twitter:

Google+:

Sneak Peeks are our way of helping readers find new books and authors and get previews. Please share and/or comment! Thank you!