I’ll Be a Writer by Matthew Hughes

I’m now reaching fifty years as a writer-for-pay. I’ve been a journalist, a speechwriter, and now a novelist and short story author.

I don’t know when I first said to myself, “I’ll be a writer.” I got into journalism after some abortive efforts toward being an advertising copywriter, a translator, and a teacher. I don’t think I ever thought I’d be a speechwriter, until I found out I was one.

I remember, just before or just after my tenth birthday, the first time I was told to write a story. This was in an honest-to-grandma, one-room, red-brick schoolhouse in rural southern Ontario. It was the fourth school I had been to that school year, the family having bounced around a bit after the summer my dad burned down the house to escape the unpayable mortgage.

I didn’t have any time to think about what I was going to write. It wasn’t a homework assignment. We were to sit there, grab our pencils, and write the story in one of those little lined exercise books they gave us in the 1950s. I didn’t think much about it but just dove in – pretty much the same way I write stories today.

It was about some kids doing a bicycle race, which strikes me as odd now because I hadn’t learned to ride a bike by then. It involved a steep hill, with a road running up it and another road that went around, and the kids split up to see who could cover the distance over or around the hill first. There was also a steep slope on the far side, a slow-moving hay wagon, and a bump on the downhill stretch. One kid ended up flying into the hay.

I don’t remember a single word I wrote, except that the steep side was described as at a 90-degree angle, which caused the teacher to say, “Really? Ninety degrees?” That was a clue to me that I should really find out what degrees were. But I remember the gist of the story because I can still see the mental pictures that were in my head when I was writing it. A lot of the way I write what I write is to put down in words the pictures I see in my head.

That was handy for me as a speechwriter, because putting pictures in other people’s heads is one of the speechwriter’s necessary arts.

After that first effort, which won me an “A” grade, despite my geometric ignorance, the next thing I can remember is a very similar assignment four years later, in Grade Nine English. The teacher told us to write a story in class, though I recall he gave us the subject, which was about the travails of a mouse. Again, all I can recall now is the image of the mouse creeping along a baseboard, and then there was some crisis, happily resolved. And, again, I received an “A.”

In Grade Ten, we had to write various pieces – essays or descriptions or book reports – and I bashed them out and continued to get high marks. By then I was well into intensive reading of science fiction and juvenile historical novels from the school and public libraries, and somewhere along the way dawned the idea that I could be a writer of such stuff myself. Indeed, I wrote a science fiction short story, long since lost, about aliens having planted a world-shattering device, aeons ago, that would detonate if our species ever reached a certain level of technology. It ended with the clock, so to speak, ticking down.

At sixteen, I was definitely committed to being a writer and even wrote the first chapter of a historical novel based upon a legend that Alexander the Great, before his death, had sent out an expedition to circumnavigate Africa. I never got beyond the first few thousand words. We were a dysfunctional working-poor family. Because my senile grandmother had been dumped on us by my father’s sister, I was sleeping on the couch. I did not have a quiet and peaceful place to work.

By the time I was counting down the weeks to the end of my last year in high school, I was still intending to be an author, but I had begun to understand that it was a risky way to make a living. Being prone, in those days, to trying to hedge my bets, I looked around to see if there were less economically perilous paths into the forest. I hit upon advertising copywriting, probably based on hapless Darren in Bewitched, and actually went downtown and talked my way into an interview with a senior guy in Vancouver’s largest advertising agency. He recommended I get a degree first.

However, by the time I was well into university, my philosophy had evolved, and I couldn’t see myself as a willing cog in the consumerist machine. After a year of thinking about being a translator (I have a knack for learning languages), I decided I would be a teacher, which would leave me two months free time every summer to pound out the great Canadian whatever. Fortunately, the teacher-training program at Simon Fraser University had an unusual way of separating the pedagogical sheep from the goats quite early. After one day of orientation, we newcomers were divided into handfuls of hopefuls and put into elementary school classrooms for six weeks of treading water in the deep end.

I learned, within days, that I did not want to spend years of my life in rooms full of children, half of whom had IQs that were less than 100. I might have done all right with bright weirdos like myself (I had an IQ of 145 back then), but not with ordinary kids. So teacher training and I had a mutual separation. Looking around, I thought, “How about being a reporter?”

In those days, you could get a job on a newspaper if you could demonstrate an ability to remain sober and write like a newspaperman. I could do both, and the way to demonstrate the latter ability was to get some clippings of things I’d written that had actually been published. I volunteered to write for the SFU student newspaper, The Peak, turning in movie reviews, book reviews, feature pieces, and oddball stuff like discovering there was only one curved line to be found in all of the gray concrete fascistic architecture of my alma mater.

My clippings book, along with a tip-off from a fellow student who had been stringing for the Vancouver Province daily, got me a once-a-week gig covering suburban municipal council meetings. I also got a stringer job with the rival Vancouver Sun, covering sports at SFU. Sportswriting was not a natural fit for me, and I was not terribly unhappy when the job disappeared after the Sun hired some of the veteran scribes of the recently defunct Toronto Telegram, and all the stringers were cut loose.

Council meetings led to feature assignments which led to a summer-staff position with the Province. That ended when, as the only reporter working on a late-August Saturday (no paper Sunday), I garbled my notes while writing up phone interviews with business types just back from Canada’s first trade fair in what was then called “Red” China. I attributed the words of the sales manager of an electronics firm to the president of a forest-products company. What sounded good coming from an electronics guy didn’t sound like the kind of thing a lumber guy should stay and my report occasioned a small flurry in the stock market. The editor and publisher had to apologize and I was booted from the premises.

Not long after, though, I landed a job as news editor on a suburban weekly, The Enterprise, serving Coquitlam, Port Coquitlam, and Port Moody. It turned out that news editor actually meant editor, since the real owner/editor, a career alcoholic, restricted himself to writing a gossip column that was mainly an excuse for a pub crawl. I can safely say that I learned a lot in the ten months I spent working for that guy, a lot of which I would have had to unlearn if I’d kept on in the newspaper business.

I was let go to make room for a guy who had bought a piece of the paper and wanted to run the newsroom. I went on unemployment insurance and wrote a truly unpublishable fantasy novel, The Fifth Age. Then I got a job on a tabloid start-up in Port Alberni, a pulp mill town in the middle of Vancouver Island. The Sounder, named after nearby Barkley Sound, was a strange place to work. Sometimes my paycheck would bounce – always a worrisome feeling. The paper was chock full of ads, which should have meant it was making tons of money, but that was not the case.

A journalist can find out what’s going on in any office in the land except one: his or her own publisher’s. It took me a while to discover that my employers were running a scam: there was a daily in Port Alberni, the Alberni Valley Times, and a not-yet-famous fellow named Conrad Black was trying to buy it. He was buying up newspapers all over the country and his practice was simple: he or his partner would phone up the owner and make an offer. If the offer was refused, he would wait a week or three, then phone again, offering more money.

This had been going on for a while with the AV Times, and a guy who worked there heard about it on the grapevine. He partnered with an ad salesman from the town’s radio station and they bought a local “shopper” – a little tabloid full of sales ads and harmless stories clipped from a filler service. The recast it as a real tabloid, rented some typographic equipment and hired some staff – including me as the sole generator of copy. (I soon talked them into hiring a fellow I’d worked with on The Enterprise to be the sports editor.)

It turned out the reason the paper was so “fat” with ads was because they were drastically undercutting the AV Times. And the reason they were doing that was so that, once the owner of the daily succumbed to Conrad Black’s chequebook, they would get bought out at the same time as the Times.

I still don’t know whether the plan worked in the end. I had signed on for a six-month engagement, and when that was up I gave my notice. I planned to freelance for the Times, do some supply teaching at the local high school (I had a suit, which seemed to be the main qualification), and write another – and better – novel. I was in the newsroom, pounding out my last column, when the campaign manager of the man who had just won the seat for the Liberals in the federal election of 1974 came in and asked me if I wanted to go to Ottawa.

I spent a week not being able to make up my mind. I finally tossed a coin – a quarter, if you want the details – and when it came up heads, I packed up wife, dog, and everything else in a VW Beetle I bought off my brother and drove 2500 miles to Ottawa and ghostwrite the MP’s newspaper column.

When I got there, to my surprise, I became what I was to be for thirty-some years: a speechwriter, hobnobbing with leaders of political parties and CEOs of billion-dollar corporations.

Which was pretty weird for a kid who grew up wearing clothes from rummage sales. But I’m sure it made me a better novelist. I’ve been a teenage hitchhiker on a lonely road with two bucks in my pocket and I’ve flown on private jets. Things many authors have to imagine are things I’ve seen close up.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Matthew Hughes writes fantasy and space opera.

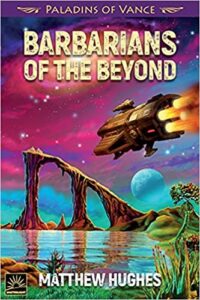

His latest novels are: A God in Chains ( Edge 2020) and Barbarians of the Beyond (Spatterlight Press, 2021), an authorized companion novel to Jack Vance’s iconic The Demon Princes quintet.

His short fiction has run in Asimov’s, F&SF, Postscripts, Lightspeed, Amazing Stories, Pulp Literature, Mythaxis, and Interzone, and in award-winning anthologies edited by George R.R. Martin and Gardner Dozois.

He has won the Endeavour and Arthur Ellis Awards, and been shortlisted for the Aurora, Nebula, Philip K. Dick, Endeavour (twice), A.E. Van Vogt, Neffy, and Derringer. He has been inducted into the Canadian Science Fiction and Fantasy.

Here’s a look at Matthew’s latest release: Barbarians of the Beyond

Twenty years ago, five master criminals known as the Demon Princes raided Mount Pleasant to enslave thousands of inhabitants in the lawless Beyond. Now Morwen Sabine, a daughter of captives, has escaped her cruel master and returns to Mount Pleasant to recover the hidden treasure she hopes will buy her parents’ freedom.

Twenty years ago, five master criminals known as the Demon Princes raided Mount Pleasant to enslave thousands of inhabitants in the lawless Beyond. Now Morwen Sabine, a daughter of captives, has escaped her cruel master and returns to Mount Pleasant to recover the hidden treasure she hopes will buy her parents’ freedom.

But Mount Pleasant has changed. Morwen must cope with mystic cultists, murderous drug-smugglers, undercover “weasels” of the Interplanetary Police Coordinating Company, and the henchmen of the vicious pirate lord who owns her parents and wants Morwen returned. So he can kill her slowly…